The career skill nobody teaches—that gets you hired

You're probably underselling yourself. Here's how to uncover what you actually bring—and describe it in ways that land interviews.

What you’ll learn

1. How understanding the word "skills" transforms how you sell yourself—especially in interviews and career changes

2. Why career changers who think they have "no skills" are almost always wrong

3. Which skills matter more as AI reshapes work—and why people skills are becoming essential

4. How to claim the highest level you can honestly demonstrate (most people undersell)

5. A practical method for uncovering your strengths through stories you already have

Most people start a job search by updating their résumé. They list job titles, responsibilities, accomplishments. But when it comes to describing their skills, the thinking gets fuzzy. They say things like "I'm a good communicator" or "I'm detail-oriented" without being able to articulate what that actually means in practice.

This fuzziness undermines everything. Your résumé lists activities instead of capabilities. Your interviews meander because you can't clearly explain what you bring. You apply to roles that don't fit because you haven't defined what you're actually good at. And you undersell yourself because you've never taken a real inventory.

Understanding how to describe your skills—precisely, specifically, at the right level—is a foundational career skill. And it starts with understanding what "skills" actually means.

The framework that changed how we think about this comes from Sidney Fine, a researcher who spent decades studying how to describe work for the U.S. Department of Labor. Fine identified three distinct types of skills that together describe what any person brings to any job. Understanding these categories—and getting specific about where you fall in each—is the foundation everything else builds on.

Sidney Fine's 3 types of skills

Fine originally called the first category "functional/transferable skills." We'll use "functional skills" going forward—since all three categories have varying degrees of transferability, the term creates more confusion than clarity.

Functional skills describe what you can do—action-oriented capabilities that transfer across industries and job titles. Someone skilled at analyzing information brings that capability whether they're in healthcare, finance, or manufacturing. The context changes; the underlying skill doesn't.

Special knowledge describes what you know—industry expertise, technical systems, regulatory frameworks, tools and platforms. Unlike functional skills, this knowledge is often specific to a domain. Knowing pharmaceutical regulations doesn't help you with construction codes. But knowledge compounds within a domain and signals depth to employers in that space.

Self-management skills describe your style—how you conduct yourself at work. These are personal traits and behaviors: reliability, initiative, flexibility, persistence. They're harder to teach than functional skills or knowledge, which is why employers value them so highly. You can train someone on a new software system. It's much harder to train someone to be dependable.

The confusion between these categories is exactly why people struggle to describe what they bring. "Attention to detail" is not a skill—it's a trait (self-management). "Analyzing data for patterns" is a skill (functional). "Knowing SQL" is knowledge (special). Each matters, but they work differently in a job search and belong in different parts of how you present yourself.

Functional skills

Of the three types, functional skills deserve the most attention—and are most often overlooked.

Special knowledge and self-management traits matter, but functional skills are where most people struggle to get specific. They're what you can do, regardless of industryand they're what you can prove through your past work

This is especially important for career changers. I hear it constantly: "I want to move into this field, but I have no skills in that area." That's almost never true. What they mean is they don't have specialized knowledge yet—they haven't learned the industry-specific tools, terminology, or frameworks. But they've likely spent years developing functional skills and self-management traits that apply regardless of industry. The project manager who wants to move from construction to tech doesn't lack skills—she's been coordinating complex projects, negotiating with stakeholders, and solving problems under pressure for a decade. Those capabilities transfer. The knowledge gap is real but learnable. The skill foundation is already there.

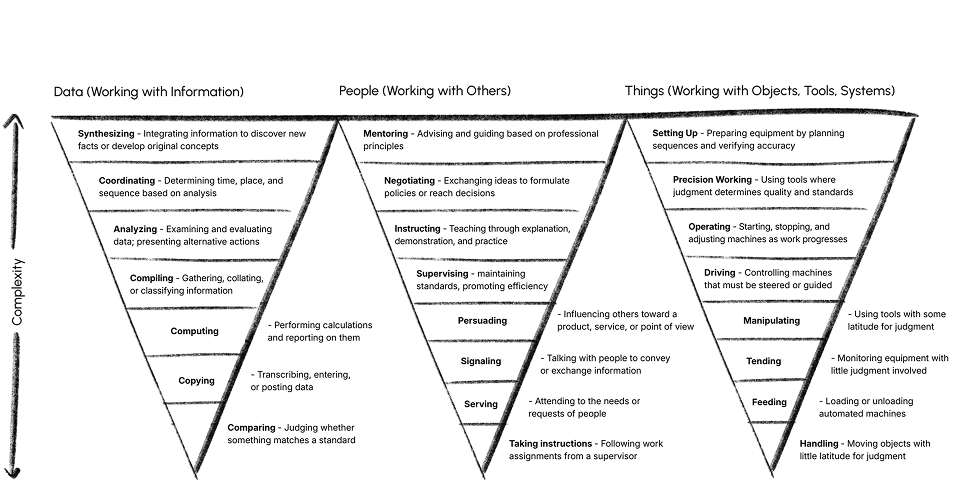

Fine organized functional skills into three categories based on what you're working with: data (information), people, and things (physical objects, tools, systems). Within each category, functions range from simple to complex. The more complex the function, the more judgment, discretion, and skill required.

Think of it as three triangles, each widest at the bottom (simple, prescribed tasks) and narrowing toward the top (complex, discretionary work). The arrow runs from prescribed at the bottom to increasingly discretionary at the top. Lower functions follow rules; higher functions require judgment.

Why the hierarchy matters for your career

Most people describe their work at a lower level than they actually performed.

A project manager who coordinated complex initiatives across multiple teams says they "organized projects." An analyst who synthesized data to develop strategic recommendations says they "analyzed data." A team lead who mentored junior staff through career decisions says they "supported the team."

This is not about modesty it's imprecision.

Each level in these hierarchies represents meaningfully different work. Comparing data is not the same as analyzing it. Taking instructions is not the same as supervising. Employers know the difference. When you describe your work at a lower level than you performed, you signal less capability than you have.

What AI Is changing

Your instinct might be to think AI is simply automating the bottom of each hierarchy—routine tasks—while humans stay safe at the top. That’s not quite what’s happening. The reality is more nuanced, and it depends on which category you’re looking at.

Data skills: AI can perform many lower-level data functions—such as copying, computing, comparing, and compiling information—far faster and more reliably than humans. It can also participate in higher-level data work by analyzing large volumes of information, synthesizing inputs, surfacing patterns, and generating possible interpretations at a speed and scale humans can’t match in practice today. But AI does not determine what matters. Humans remain responsible for framing the problem, imagining new possibilities, exercising judgment, evaluating which interpretations hold together, shaping the output, and deciding what should be acted on. AI changes how data work is done, but it doesn’t eliminate human judgment—it raises the bar for it. As routine data tasks are absorbed by machines and analysis accelerates, human value shifts toward higher-order thinking: abstraction, discernment, sense-making, and responsibility for outcomes.

Things skills: Robotics and automation continue to advance, but replacing physical work is often harder than replacing cognitive work. Automating tasks in the physical world usually requires building and maintaining machines with moving parts, which is expensive and only makes sense in certain settings. In highly structured environments—like factories or warehouses, where objects are standardized and processes are repeatable—automation works well and continues to expand. But many physical jobs, such as plumbing, electrical work, or hairdressing, take place in unstructured, unpredictable environments and require constant adaptation. It’s often easier to automate large portions of what an accountant does than to replace a plumber or a hairdresser. For these reasons, automation in “things” work is advancing more slowly than in data.

People skills: Some people-facing work, such as basic customer service or scripted support, is increasingly automated. But these roles sit at the lower end of the people hierarchy, where interactions are transactional and judgment is limited. Higher-order people skills—mentoring someone through a difficult decision, negotiating complex agreements, resolving conflict, or adapting instruction to the individual—depend on trust, empathy, and contextual judgment. These functions are harder to automate because they involve responsibility for other people and outcomes that can’t be fully specified in advance. As more data and routine interactions are handled by machines, these higher-order people skills become a stronger differentiator, not a weaker one.

What we can conclude is that AI doesn’t simply automate “low-skill” work and protect “high-skill” work. It cuts across jobs unevenly, reshaping most roles rather than eliminating them outright. As machines take on more execution and analysis, human work shifts toward judgment, coordination, and sense-making. In many cases, the economic logic isn’t cost reduction but value creation: pairing human judgment with machine capability to achieve outcomes neither could produce alone.

Don't confuse skills and traits

Two common mistakes weaken how people describe their value: confusing traits with skills, and being vague about both.

Skills vs traits

Skills and traits describe different kinds of value, but they’re often mixed together. A skill is a capability—something you can do. A trait describes how you conduct yourself while doing that work. Think of traits as your style or way of working. For example, two managers may both be skilled at leading teams, but how they lead can look very different—one relies on structure and clear processes, while the other leads through flexibility and relationships. The skill is the same; the style—how the work gets done—is different

Skills are best described with verbs. They are observable, testable, and teachable—things like analyzing data, coordinating projects, or facilitating meetings. Traits are descriptive qualities—adjectives like dependable, flexible, or detail-oriented—that reflect patterns in how you work rather than specific actions.

Side note: This distinction matters a lot in practice. When we recruit for clients, we’re not just matching skills to a role—we’re matching styles and traits to the environment. A highly structured leader can be exactly right for a stable organization, but the wrong fit during a period of rapid change. When a company is navigating uncertainty or transformation, we look for people whose style reflects adaptability, comfort with ambiguity, and strong relationship-building. The same skill set can succeed or fail depending on the moment and context

Both skills and traits can transfer across roles and industries, but they function differently in a job search. Skills show what you can produce. Traits signal how you’re likely to work while producing it. When people confuse the two, they often sound vague even when they’re capable.

Here's the difference:

The left column describes your style. The right column describes capabilities you can demonstrate through evidence. Both matter—but they belong in different parts of how you present yourself, and only skills can be directly tested or proven in a hiring process.

Vague vs. Specific

Another issue we see throughout the hiring process is vague descriptions of skills and traits, which strip away the real value someone brings.

“I’m a good communicator” is the classic example. It sounds positive, but it’s vague and it could mean very different things, such as:

- Writing clearly for different audiences

- Presenting ideas to groups

- Teaching complex concepts through explanation and demonstration

- Negotiating contract terms with stakeholders

- Facilitating meetings to reach decisions

- Persuading customers to buy

These are meaningfully different skills, often at different levels of complexity. Saying “good communicator” hides which ones you actually have. It’s like saying “good with computers” when what you really mean is “can build financial models in Excel” or “can write Python scripts to automate data processing.”

The fix is specificity. When you think about your skills, push yourself to describe them more clearly. Ask what the skill looks like in practice. Not “good communicator,” but “can explain technical concepts to non-technical audiences.” Not “detail-oriented,” but “can analyze financial data to catch discrepancies before they become problems.”

When you describe what you bring, ask yourself: Is this specific enough that someone could picture me doing it? If not, push further.

How to discover your own unique skills & traits: The 5 stories method

Understanding the framework is one thing. Applying it to yourself is harder.

The problem is that your skills are invisible to you. You've been using them so long they feel like breathing—not capabilities that others might lack. This is why people say "I don't really have any special skills" while colleagues watch them do things they couldn't do themselves.

The fix is to work backward from evidence. Instead of staring at a list of skills and trying to decide which ones apply to you, start with stories from your own experience and extract the skills from them. Plus, practicing stories will give you solid foundation and practice for answering behavioral based interview questions.

Step 1: Identify five stories

Think of at least five moments from your work or life where you felt genuine pride. These might be accomplishments—projects you completed, goals you hit, things you built. Or they might be challenges you overcame—problems you solved, obstacles you pushed through, fears you faced.

The stories don't need to be dramatic. They need to be real moments where you thought "I did that" and felt good about it.

Step 2: Write each story in detail

For each one, write a few paragraphs describing what happened. Include the situation or challenge you faced, what you actually did (specific actions), what obstacles you encountered, how it turned out, and why it mattered to you.

Step 3: Analyze each story for skills

Go through each story and identify:

· Data skills: What did you do with information? Did you analyze, compile, synthesize, coordinate?

· People skills: What did you do with or for others? Did you teach, persuade, negotiate, mentor, supervise?

· Things skills: What did you do with tools, systems, or physical objects? Did you build, operate, troubleshoot, set up?

· Self-management traits: What does the story reveal about how you conduct yourself?

Step 4: Look for patterns

After analyzing all five stories, patterns emerge. The same skills show up repeatedly. Those recurring capabilities are your functional skills—the things you do well, probably without even thinking about it.

Example: Analyzing a real story

Here's how this works in practice.

The story: “Early in my career, I was terrified of public speaking. I knew it was a critical skill—and that avoiding it would eventually limit my growth. So instead of dodging it, I made a deliberate (and uncomfortable) decision. While still in university, I saved money from my part-time waitressing job and enrolled in a Dale Carnegie public speaking course. It was expensive and a real financial risk at the time. During the first session, I walked off the stage mid-speech. I wanted to quit. Instead, I came back the next week. And the week after that. I completed the full 12-week program—and somewhere along the way, I started to enjoy it. When I finished, Dale Carnegie offered me my first professional job.

What this story reveals:

Data skills:

There is evidence of planning and basic quantitative reasoning. She had to budget her waitressing income, calculate how much she could realistically save, and plan the timing of her enrollment to afford the course. This reflects the ability to work with information, evaluate constraints, and make a deliberate financial decision.

People skills:

By the end of the story, she had developed public speaking and communication skills—first learning to speak to groups, then signaling confidence, and eventually instructing others. The story is not about innate people skills, but about intentionally building a people capability she did not previously have, which later became a foundation for teaching and training.

Things skills:

Things skills are not prominent in this story, and that is acceptable. Not every experience will touch all skill categories, and their absence here does not reduce the value of the signal.

Self-management traits:

This is where the story is richest. It reveals someone who is growth-oriented, having identified a personal weakness and chosen to address it. It shows resourcefulness in finding a way to pay for training on a limited budget, persistence in returning after walking off stage mid-speech, and initiative in taking action without being directed. It also demonstrates a willingness to invest in self-development by spending personal money to build a capability, and courage in facing fear rather than avoiding it.

The insight:

This story demonstrates how self-management traits—her style—enabled the development of a critical functional skill: public speaking. The traits came first and created the conditions for the capability to emerge. This is why both skill and self-management categories matter, and why they must be evaluated together rather than in isolation.

Your Turn

Before moving on, complete this exercise:

1. List five stories of accomplishments or challenges that made you feel pride

2. Write each one out in a few paragraphs with specific details

3. Analyze each for skills: What data/people/things skills did you use? What traits did you demonstrate?

4. Look for patterns: Which skills and traits appear across multiple stories?

The skills that show up repeatedly are your foundation. They're what you bring—not what your job title says, not what your industry expects, but the actual capabilities you've demonstrated through evidence.

Once you can describe what you bring in specific, accurate language, everything else in your job search gets clearer. Your résumé tells a coherent story. Your interviews have substance. You can evaluate whether a role actually fits what you do well—and what you want to keep doing.

Most people never do this work. They rely on vague labels, underestimate their strengths, and end up in an unfocused job search. The ones who do the work gain clarity and agency. They know where they fit, how to talk about their impact, and how to choose roles that actually align with their strengths.

FAQ’s

Functional skills are capabilities—what you can do (verbs like analyzing, teaching, negotiating). They describe how you work, not where you've worked. Special knowledge is information—what you know (nouns like healthcare regulations, Python, financial markets). It's often specific to an industry or domain.

Look at the amount of judgment and discretion your work requires. If you follow prescribed rules and procedures, you're at lower levels. If you make decisions based on analysis, interpret ambiguous situations, or guide others through complex problems, you're at higher levels. The key question: how much latitude do you have to determine how the work gets done?

Absolutely. Most people are. You might be at a high level working with data (synthesizing, coordinating) but a lower level working with things (tending, manipulating). Your profile across all three categories—data, people, and things—describes your overall skill set.

The stories don't need to be dramatic. They need to be real. A story about figuring out how to organize a chaotic filing system reveals analytical and compiling skills. A story about helping a frustrated coworker work through a problem reveals people skills. The five stories method works because patterns emerge across multiple stories, not because any single story is extraordinary.

Strengths assessments typically identify preferences and tendencies—how you naturally think and behave. Sidney Fine's framework identifies capabilities—what you can demonstrably do. Both are useful, but they answer different questions. Strengths tell you how you're wired. Skills tell you what you can offer an employer.